This text is available as a pdf document

(309 kB) here - Heraclitus

Heraclitus

Some Translations and

Notes

Contents

- Translations of Some Fragments Attributed to

Heraclitus

- The Poetry of Heraclitus - Notes on Fragment B1

- Some Notes on Πόλεμος and Δίκη in Heraclitus B80

- Notes on Heraclitus Fragment 112

- Notes on Heraclitus Fragment 123

- Notes on Heraclitus Fragment 53

- The Abstraction of Change as Opposites and

Dialectic

- The Principle of Δίκα

Translations of Some Fragments Attributed to Heraclitus

Preface

As explained in the notes that originally accompanied the

translations, I have deliberately transliterated (instead of

translated) πόλεμος, and left δίκη as δίκη

- because both πόλεμος and δίκη should be

regarded like ψυχή (psyche/Psyche) as terms or as

principles in their own right (hence the capitalization), and thus

imply, suggest, and require, interpretation and explanation,

something especially true, in my opinion, regarding δίκη.

To render such Greek terms blandly by English terms such as 'war'

and 'justice' - which have their own now particular meaning(s) -

is in my view erroneous and somewhat lackadaisical. δίκη

for instance could be, depending on context: the custom(s) of a

folk, judgement (or Judgement personified), the natural and the

necessary balance, the correct/customary/ancestral way, and so on.

The notes to the translations are included below.

David Myatt

2012

(Revised February 2013)

Fragment 1

τοῦ δὲ λόγου τοῦδ᾽ ἐόντος ἀεὶ ἀξύνετοι γίνονται

ἄνθρωποι καὶ πρόσθεν ἢ ἀκοῦσαι καὶ ἀκούσαντες τὸ πρῶτον·

γινομένων γὰρ πάντων κατὰ τὸν λόγον τόνδε ἀπείροισιν ἐοίκασι,

πειρώμενοι καὶ ἐπέων καὶ ἔργων τοιούτων, ὁκοίων ἐγὼ διηγεῦμαι

κατὰ φύσιν διαιρέων ἕκαστον καὶ φράζων ὅκως ἔχει· τοὺς δὲ ἄλλους

ἀνθρώπους λανθάνει ὁκόσα ἐγερθέντες ποιοῦσιν, ὅκωσπερ ὁκόσα

εὕδοντες ἐπιλανθάνονται

Although this naming and expression [which I explain]

exists, human beings tend to ignore it, both before and after they

have become aware of it. Yet even though, regarding such naming

and expression, I have revealed details of how Physis has been

cleaved asunder, some human beings are inexperienced concerning

it, fumbling about with words and deeds, just as other human

beings, be they interested or just forgetful, are unaware of what

they have done.

Fragment 36

ψυχῆισιν θάνατος ὕδωρ γενέσθαι, ὕδατι δὲ θάνατος γῆν

γενέσθαι, ἐκ γῆς δὲ ὕδωρ γίνεται, ἐξ ὕδατος δὲ ψυχή.

Where the water begins our living ends and where earth begins

water ends, and yet earth nurtures water and from that water,

Life.

Fragment 39

ἐν Πριήνηι Βίας ἐγένετο ὁ Τευτάμεω, οὗ πλείων λόγος

ἢ τῶν ἄλλων

In Priene was born someone named and recalled as most worthy –

Bias, that son of Teutamas

Fragment 43

ὕβριν χρὴ

σβεννύναι μᾶλλον

ἢ πυρκαϊὴν

Better to deal with your hubris before you confront that

fire

Fragment 52

αἰὼν παῖς ἐστι παίζων πεσσεύων· παιδὸς ἡ βασιληίη

For Aeon, we are a game, pieces moved on some board: since, in

this world of ours, we are but children.

Fragment 53

Πόλεμος πάντων μὲν πατήρ ἐστι, πάντων δὲ βασιλεύς, καὶ τοὺς

μὲν θεοὺς ἔδειξε τοὺς δὲ ἀνθρώπους, τοὺς μὲν δούλους ἐποίησε

τοὺς δὲ ἐλευθέρους.

Polemos our genesis, governing us all to bring forth some gods,

some mortal beings with some unfettered yet others kept bound.

Fragment 64

τὰ δὲ πάντα οἰακίζει Κεραυνός

All beings are guided by Lightning

Fragment 80

εἰδέναι δὲ χρὴ τὸν πόλεμον ἐόντα ξυνόν, καὶ δίκην

ἔριν, καὶ γινόμενα πάντα κατ΄ ἔριν καὶ χρεώμενα [χρεών]

One should be aware that Polemos pervades, with discord δίκη,

and that beings are naturally born by discord.

Fragment 112

σωφρονεῖν ἀρετὴ μεγίστη, καὶ σοφίη ἀληθέα

λέγειν καὶ ποιεῖν κατὰ φύσιν ἐπαίοντας

Most excellent is balanced reasoning, for that skill can tell

inner character from outer.

Fragment 123

Φύσις κρύπτεσθαι φιλεῖ

Concealment accompanies Physis

From Diogenes Laërtius - Lives

of Eminent Philosophers

πάντα δὲ

γίνεσθαι καθ᾽

εἱμαρμένην καὶ

διὰ τῆς ἐναντιοδρομίας ἡρμόσθαι

τὰ ὄντα

(ix. 7)

All by genesis is appropriately apportioned [separated into

portions] with beings bound together again by enantiodromia

Note: I have used here a transliteration of the compound

Greek word ἐναντιοδρομίας rather

than given a particular translation, since the term enantiodromia

in my view suggests the uniqueness of expression of the original,

and which original in my view is not adequately, and most

certainly not accurately, described by a usual translation such as

'conflict of opposites'. Rather, what is suggested is

'confrontational contest' - that is, by facing up to the

expected/planned/inevitable contest. Interestingly, Carl Jung -

who was familiar with the sayings of Heraclitus - used the term

enantiodromia to describe the emergence of a trait (of character)

to offset another trait and so restore a certain psychological

balance within the individual. For further

details, refer to my essay The Change of Enantiodromia.

The Poetry of Heraclitus

Part One - Some Notes on λόγος in Fragment B1

In respect of fragments 80 and 112 I have suggested that it is

incorrect to interpret

πόλεμος simplistically as 'war',

strife, or kampf

[1] and that, instead

of using such words, it should be transliterated so as to name a

distinct philosophical principle that requires interpretation and

explanation with particular reference to Hellenic culture and

philosophy. For, more often than not, such common English words as

'war' are now understood in a non-Hellenic, non-philosophical,

context and explained in relation to some ideated opposite; and in

the particular case of the term 'war', for example, in contrast to

some-thing named, explained, or defined, as 'peace' or a state of

non-belligerence.

In respect of fragment 1

[2], does

λόγος

suggest a philosophical principle - Logos - and therefore should

it, like

πόλεμος, be transliterated and thus be

considered as a basic principle of the philosophy of Heraclitus,

or at least of what, of that philosophy or weltanschauung, we can

adduce from the textual fragments we possess? Or does

λόγος,

as I suggested in respect of fragment 112 and 123

[3]

imply:

both a naming (denoting), and a

telling – not a telling as in some abstract explanation

or theory, but as in a simple describing, or recounting, of what

has been so denoted or so named. Which is why, in fragment 39,

Heraclitus writes:

ἐν Πριήνηι Βίας ἐγένετο ὁ Τευτάμεω, οὗ πλείων λόγος ἢ

τῶν ἄλλων [4]

and why, in respect of λέγειν, Hesiod wrote:

ἴδμεν ψεύδεα πολλὰ λέγειν ἐτύμοισιν ὁμοῖα,

ἴδμεν δ᾽, εὖτ᾽ ἐθέλωμεν, ἀληθέα γηρύσασθαι [5]

I contend that fragment 1 also suggests a denoting, in the sense

of expressing some-thing by denoting it or describing it by a

'name'. That is, that

λόγος here does not refer here to

what has often be termed Logos, and that the 'ambiguous'

ἀεὶ

[6] is not really ambiguous at all.

For one has to, in my view, take account of the fact that there is

poetry in Heraclitus; a rather underrated style that sometimes led

others to incorrectly describe him as

ὁ

σκοτεινός, the ambiguous (or the obtuse) one, and

led Aristotle to write:

τὰ γὰρ Ἡρακλείτου

διαστίξαι ἔργον διὰ

τὸ ἄδηλον

εἶναι ποτέρῳ πρόσκειται,

τῷ ὕστερον ἢ τῷ

πρότερον, οἷον ἐν

τῇ ἀρχῇ αὐτῇ

τοῦ συγγράμματος:

φησὶ γὰρ "τοῦ

λόγου τοῦδ᾽ ἐόντος

ἀεὶ ἀξύνετοι ἄνθρωποι γίγνονται":

ἄδηλον γὰρ τὸ

ἀεί, πρὸς ποτέρῳ

δεῖ διαστίξαι. [6]

It is the poetic style of Heraclitus that I have tried, however

badly, to express in my often non-literal and rather idiosyncratic

translations/interpretations of some of the fragments attributed

to him. Hence my interpretation of the first part

[8]

of fragment 1, published in 2012:

Although this naming and expression [which I explain]

exists – human beings tend to ignore it, both before and after

they have become aware of it.

The 'which I explain' is implicit in the sense of

λόγος here

as a naming and expression by a particular individual, contrasted

(as often with Heraclitus) rather poetically with a generality; in

this instance, contrasted with human beings - 'men' - in general,

and with "tend to" modifying the sense of

ἀεὶ from the

strident, bland, 'always' to a more poetic expression of human

beings having an apparently rather irreconcilable tendency - for

now (at least) and certainly as in the past - to ignore (or forget

or not understand) certain things, even after matters have been

explained to them (they have heard the explanation) and even after

they have discovered certain truths for themselves.

David Myatt

January 2013

[1] qv.

The Abstraction of Change as Opposites and Dialectic,

and

Some Notes on Πόλεμος and Δίκη in

Heraclitus B80

As mentioned in

The Abstraction of Change as Opposites and

Dialectic:

"In addition, Polemos was originally the δαίμων

[not the god] of kindred strife, whether familial, or of one's πόλις (one's clan and their places

of dwelling). Thus, to describe Polemos, as is sometimes done,

as the god of conflict (or war), is doubly incorrect."

[2] qv. Sextus Empiricus:

Advenus Mathematicos VII. 132

The text of fragment 1 (with the reading τοῦδ᾽ ἐόντος and not τοῦ

δέοντος) is:

τοῦ δὲ λόγου τοῦδ᾽ ἐόντος ἀεὶ ἀξύνετοι γίνονται ἄνθρωποι καὶ

πρόσθεν ἢ ἀκοῦσαι καὶ ἀκούσαντες τὸ πρῶτον· γινομένων γὰρ πάντων

κατὰ τὸν λόγον τόνδε ἀπείροισιν ἐοίκασι, πειρώμενοι καὶ ἐπέων καὶ

ἔργων τοιούτων, ὁκοίων ἐγὼ διηγεῦμαι κατὰ φύσιν διαιρέων ἕκαστον

καὶ φράζων ὅκως ἔχει· τοὺς δὲ ἄλλους ἀνθρώπους λανθάνει ὁκόσα

ἐγερθέντες ποιοῦσιν, ὅκωσπερ ὁκόσα εὕδοντες ἐπιλανθάνονται.

[3] Regarding 123

- Φύσις κρύπτεσθαι φιλεῖ -

qv.

Physis, Nature, Concealment, and Natural Change,

e-text 2010

[4] "In Priene was born someone named and recalled as most

worthy – Bias, that son of Teutamas."

[5]

We have many ways to conceal – to name – certain things

And the skill when we wish to expose their meaning

[6] Aristotle:

Ars Rhetorica Book 3, chapter 5 [1407b]

[7]

θεοί - and

Μοῖραι τρίμορφοι μνήμονές τ᾽ Ἐρινύες

- permitting I may in the not too distant future endeavour to

translate/interpret the rest of the fragment.

°°°

Acknowledgements: The genesis of this

article was a personal reply sent to Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi of

Oxford university, in response to questions concerning ἀεὶ and

my rather idiosyncratic interpretation of the first part of

the text of fragment 1.

The Poetry of Heraclitus

Part Two - Some Notes on Physis and Forgetfulness in

Fragment B1

τοῦ δὲ λόγου τοῦδ᾽ ἐόντος ἀεὶ ἀξύνετοι γίνονται

ἄνθρωποι καὶ πρόσθεν ἢ ἀκοῦσαι καὶ ἀκούσαντες τὸ πρῶτον·

γινομένων γὰρ πάντων κατὰ τὸν λόγον τόνδε ἀπείροισιν ἐοίκασι,

πειρώμενοι καὶ ἐπέων καὶ ἔργων τοιούτων, ὁκοίων ἐγὼ διηγεῦμαι

κατὰ φύσιν διαιρέων ἕκαστον καὶ φράζων ὅκως ἔχει· τοὺς δὲ ἄλλους

ἀνθρώπους λανθάνει ὁκόσα ἐγερθέντες ποιοῦσιν, ὅκωσπερ ὁκόσα

εὕδοντες ἐπιλανθάνονται

Translation

My translation of the fragment is:

Although this naming and expression [which I explain]

exists, human beings tend to ignore it, both before and after

they have become aware of it. Yet even though, regarding such

naming and expression, I have revealed details of how Physis has

been cleaved asunder, some human beings are inexperienced

concerning it, fumbling about with words and deeds, just as

other human beings, be they interested or just forgetful, are

unaware of what they have done.

Comments

1. For the first part - τοῦ δὲ λόγου τοῦδ᾽ ἐόντος ἀεὶ ἀξύνετοι

γίνονται ἄνθρωποι καὶ πρόσθεν ἢ ἀκοῦσαι καὶ ἀκούσαντες τὸ πρῶτον -

refer to

Part One - Some Notes on λόγος in Fragment B1

2. I take the sense of διαιρέων here somewhat poetically to

suggest not the ordinary 'divide' but the more expressive

'cleave', with it being undivided Physis that is cleaved into

parts by "such naming and expression" as Heraclitus has revealed.

That is, Heraclitus is not saying that he has described or

expressed each thing 'in accordance with its true nature' (or

divided things correctly, or something of the kind) but rather

that the process of naming and categorization is or has divided

Physis, obscuring the true nature of Being and beings, and it is

this process, this obscuring, or concealment. of Physis - of

cleaving it into separate parts or each thing, 'each' contrasted

with a generality

[1] - that he has

revealed and is mentioning here, as he mentioned it in fragment

123:

Φύσις κρύπτεσθαι φιλεῖ

Concealment accompanies Physis [2]

Which is why I have transliterated

Φύσις as referring

to a general philosophical principle of the philosophy of

Heraclitus, or at least of what, of that philosophy or

weltanschauung, we can adduce from the textual fragments we

possess.

3. In respect of πειρώμενοι καὶ ἐπέων καὶ ἔργων τοιούτων, the

Homeric usage

[3] is, for me,

interesting as it implies a proverbial kind of saying rather than

just 'words' and 'deeds':

Τηλέμαχ᾽, οὐδ᾽ ὄπιθεν κακὸς ἔσσεαι οὐδ᾽ ἀνοήμων,

εἰ δή τοι σοῦ πατρὸς ἐνέστακται μένος ἠύ,

οἷος κεῖνος ἔην τελέσαι ἔργον τε ἔπος τε:

Telemachus – you will not be unlucky nor lacking in resolution

If you hereafter instill into yourself the determination of

your father

Whose nature was to accomplish those deeds he said he would.

Furthermore, I take the sense here of πειρώμενοι poetically to

suggest a "fumbling about" - as the inexperienced often fumble

about and experiment until, often by trial and error, they have

gained sufficient experience to understand and know what they are

doing and what is involved, which rather reminds one of a saying

of Pindar

[4]:

γλυκὺ δὲ πόλεμος ἀπείροισιν, ἐμπείρων δέ τις

ταρβεῖ προσιόντα νιν καρδίᾳ περισσῶ

4. Given that, as mentioned in Part One, there is poetry in

Heraclitus, I am inclined to avoid the literal, and usual,

understanding of ἐγερθέντες and εὕδοντες, particularly given the

foregoing πειρώμενοι καὶ ἐπέων καὶ ἔργων τοιούτων which renders

such a literal understanding not only out of context and

disjointed but decidedly odd. Human beings forgetting things when

they sleep? If, however, and for example,

ἐγείρω here

poetically suggests alertness, an interest or excitement - as

ἤγειρεν

in the Agamemnon suggests an alertness and excitement, an interest

in what has occurred, and thence the kindling of a pyre

[5]

- then there is, as often in Heraclitus, a flowing eloquence and

that lack of discordance one might expect of an aphorism

remembered and recorded long after the demise of its author.

David Myatt

February 2013

Notes:

[1] As in Homer et al, for example Iliad, Book VII, 215 -

Τρῶας δὲ τρόμος αἰνὸς ὑπήλυθε γυῖα ἕκαστον

But over the Trojans, a strange fear, to

shake the limbs of each one there

[2] qv. my

Physis, Nature, Concealment, and Natural Change

[Notes on Heraclitus fragment 123], e-text 2010

[3] Odyssey, Book II, 272

[4] Fragment 110

[5] Aeschylus, Agamemnon, 296-299

σθένουσα λαμπὰς δ᾽ οὐδέπω μαυρουμένη,

ὑπερθοροῦσα πεδίον Ἀσωποῦ, δίκην

φαιδρᾶς σελήνης, πρὸς Κιθαιρῶνος λέπας

ἤγειρεν ἄλλην ἐκδοχὴν πομποῦ πυρός.

The torch, vigorous and far from extinguished,

Bounded over the Asopian plain

To the rocks of Cithaeron as bright as the moon

So that the one waiting there to begin that fire, jumped up

Note that here the watchman is not awakened from sleep.

Some Notes on Πόλεμος and Δίκη

in Heraclitus B80

εἰδέναι δὲ χρὴ τὸν πόλεμον ἐόντα ξυνόν, καὶ δίκην

ἔριν, καὶ γινόμενα πάντα κατ΄ ἔριν καὶ χρεώμενα [χρεών].

Fragmentum 80.

This fragment, attributed to Heraclitus, is generally considered to

mean something rather abstract such as: war is everywhere and strife

is justice and all that is arises and passes away because of strife.

That is, πόλεμος is regarded as a synonym for

either kampf, or more generally, for war. However, I incline toward

the view that this older understanding of - the accepted rendition

of - πόλεμος is a misinterpretation,

and that rather than kampf (struggle), or a general type of strife,

or what we now associate with the term war, πόλεμος

implies what I have elsewhere termed the acausality (a simultaneity)

[1] beyond our causal ideation, and which ideation has separated

object from subject, and often abstracted them into seemingly

conflicting opposites [2]. Hence my particular interpretation of

Fragmentum 53:

Πόλεμος πάντων μὲν πατήρ ἐστι, πάντων δὲ βασιλεύς, καὶ τοὺς

μὲν θεοὺς ἔδειξε τοὺς δὲ ἀνθρώπους, τοὺς μὲν δούλους ἐποίησε

τοὺς δὲ ἐλευθέρους.

Polemos our genesis, governing us all to bring forth some gods,

some mortal beings with some unfettered yet others kept bound.

Hence my interpretation of Fragment 80 - εἰδέναι δὲ χρὴ τὸν

πόλεμον ἐόντα ξυνόν, καὶ δίκην ἔριν, καὶ γινόμενα πάντα κατ΄ ἔριν

καὶ χρεώμενα [χρεών] - as:

One should be aware that Polemos pervades, with discord

δίκη, and that beings are naturally born by discord. [3]

Here, I have deliberately transliterated (instead of translated) πόλεμος,

and left δίκη as δίκη - because both πόλεμος

and δίκη (written Πόλεμος and, I suggest, Δίκα)

should be regarded, like ψυχή (psyche/Psyche) as

terms or as principles in their own right (hence the

capitalization), and thus imply, suggest, and require,

interpretation and explanation, something especially true, in my

opinion, regarding Δίκα. To render them blandly by English

terms such as 'war' and 'justice' - which have their own now

particular meaning(s) - is in my view erroneous and somewhat

lackadaisical. δίκη for instance could be, depending on

context: the custom(s) of a folk, judgement (or Judgement

personified), the natural and the necessary balance, the

correct/customary/ancestral way, and so on.

In respect of Δίκα,

I write it thus to intimate a new, a particular and numinous,

philosophical principle, and differentiate it from the more general

δίκη. As a numinous principle, or axiom, Δίκα

thus suggests what lies beyond and what was the genesis of δίκη

personified as the goddess, Judgement - the goddess of natural

balance, of the ancestral way and ancestral customs.

Thus, Δίκα implies the balance, the reasoned judgement,

the thoughtful reasoning - σωφρονεῖν - that πάθει

μάθος brings and restores, and which accumulated πάθει

μάθος of a particular folk or πόλις

forms the basis for their ancestral customs. δίκη is

therefore, as the numinous principle Δίκα, what may be

said to be a particular and a necessary balance between ἀρετή

and ὕβρις - between the ὕβρις that often results

when the personal, the natural, quest for ἀρετή becomes

unbalanced and excessive.

That is, when ἔρις (discord) is or becomes δίκη -

as suggested by Heraclitus in Fragment 80.

In respect of Πόλεμος,

it is perhaps interesting that in the recounted tales of Greek

mythology attributed to Aesop, and in circulation at the time of

Heraclitus, a personified πόλεμος (as the δαίμων

of kindred strife) married a personified ὕβρις (as the δαίμων

of arrogant pride) [4] and that it was a common folk belief that πόλεμος

accompanied ὕβρις - that is, that Polemos followed Hubris

around rather than vice versa, causing or bringing ἔρις.

As a result of ἔρις, there often arises πάθει μάθος

- that practical and personal knowing, that reasoned understanding

which, according to Aeschylus [5] is the new law, the new

understanding, given by Zeus to replace the older more religious and

dogmatic way of fear and dread, often viewed as Μοῖραι

τρίμορφοι μνήμονές τ᾽ Ἐρινύες [6]. A new understanding which

Aeschylus saught to explain in the Oresteia.

Therefore one can perhaps understand and appreciate the true and

acausal nature of Πόλεμος which, as suggested by Fragment

53, is a natural principle (or 'energy' or a manifestation of Being)

which affects, or governs, all mortals and which, as suggested by

Fragment 80, causes the manifestation of beings from Being (the

causal separation of beings) and which natural separation results in

ἔρις and thence, as suggested by Fragment 123 [7] a return to

Being; a return which can result, as suggested by Fragment 112 [8]

arise from thoughtful reasoning [σωφρονεῖν] - and which

thoughtful, balanced, reasoning can incline us toward not committing

ὕβρις.

David Myatt

April 2011

Notes

[1] For the axiom of acausality, see my Introduction to The

Philosophy of The Numen.

[2] For an outline of opposites, refer to my essay The

Abstraction of Change as Opposites and Dialectic.

[3] Some alternative renderings of this fragment are:

One should be aware that polemos is pervasive; and discord δίκη,

and that beings [our being] quite naturally come-into-being

through discord

One should be aware that polemos pervades; with discord δίκη,

and that all beings are begotten because of discord.

[4] A δαίμων is not one of the pantheon of major Greek gods

- θεοί - but rather a lesser type of divinity who might be

assigned by those gods to bring good fortune or misfortune to human

beings and/or watch over certain human beings and especially

particular numinous (sacred) places.

Furthermore, Polemos was originally the δαίμων of kindred

strife, whether familial, or of one's πόλις

(one's clan and their places of dwelling). Thus, to describe

Polemos, as is sometimes done, as the god of conflict (or war), is

doubly incorrect.

[5] Agamemnon,174-183. qv. my essay, From Aeschylus To The

Numinous Way - The Numinous Authority of πάθει μάθος

[6] Aeschylus (attributed), Prometheus Bound, 515-6

[7] Φύσις κρύπτεσθαι φιλεῖ - Concealment accompanies

Physis. See my Physis, Nature, Concealment, and Natural

Change.

[8] σωφρονεῖν ἀρετὴ μεγίστη, καὶ σοφίη ἀληθέα λέγειν καὶ ποιεῖν

κατὰ φύσιν ἐπαίοντας

For this fragment, see my essay The Balance of Physis – Notes on

λόγος and ἀληθέα in Heraclitus.

The Balance of Physis – Notes on λόγος

and ἀληθέα in Heraclitus

Part One – Fragment 112

σωφρονεῖν ἀρετὴ μεγίστη, καὶ σοφίη ἀληθέα λέγειν καὶ ποιεῖν

κατὰ φύσιν ἐπαίοντας. [1]

Most excellent is balanced reasoning, for that skill can tell

inner character from outer.

This fragment is interesting because it contains what some regard

as the philosophically important words σωφρονεῖν, ἀληθέα,

φύσις and λόγος.

The fragment suggests that what is most excellent [ ἀρετὴ

] is thoughtful reasoning [σωφρονεῖν] – and such

reasoning is both (1) to express (reveal) meaning and (2) that

which is in accord with, or in sympathy with, φύσις –

with our nature and the nature of Being itself.

Or, we might, perhaps more aptly, write – such reasoning is both

an expressing of inner meaning (essence), and expresses our own,

true, nature (as thinking beings) and the balance, the nature, of

Being itself.

λέγειν [λόγος] here does not suggest what we

now commonly understand by the term 'word'. Rather, it suggests

both a naming (denoting), and a telling – not

a telling as in some abstract explanation or theory, but as in a

simple describing, or recounting, of what has been so denoted or

so named. Which is why, in fragment 39, Heraclitus writes:

ἐν Πριήνηι Βίας ἐγένετο ὁ Τευτάμεω, οὗ πλείων λόγος ἢ τῶν

ἄλλων [2]

and why, in respect of λέγειν, Hesiod [see below under ἀληθέα]

wrote:

ἴδμεν ψεύδεα πολλὰ λέγειν ἐτύμοισιν ὁμοῖα,

ἴδμεν δ᾽, εὖτ᾽ ἐθέλωμεν, ἀληθέα γηρύσασθαι [3]

φύσις here suggests the Homeric [4] usage of

nature, or character, as in Herodotus (2.5.2):

Αἰγύπτου γὰρ φύσις ἐστὶ τῆς χώρης τοιήδε

but also suggests Φύσις (Physis) – as in fragment

123; the natural nature of all beings, beyond their outer

appearance.

ἀληθέα – commonly translated as truth – here

suggests (as often elsewhere) an exposure of essence, of

the reality, the meaning, which lies behind the outer (false)

appearance that covers or may conceal that reality or meaning, as

in Hesiod (Theog, 27-28):

ἴδμεν ψεύδεα πολλὰ λέγειν ἐτύμοισιν ὁμοῖα,

ἴδμεν δ᾽, εὖτ᾽ ἐθέλωμεν, ἀληθέα γηρύσασθαι [3]

σωφρονεῖν here suggests balanced (or

thoughtful, measured) reasoning – but not according to some

abstract theory, but instead a reasoning, a natural way or manner

of reasoning, in natural balance with ourselves, with our nature

as thinking beings.

Most importantly, perhaps, it is this σωφρονεῖν which

can incline us toward not committing ὕβρις (hubris;

insolence), which ὕβρις is a going beyond the natural

limits, and which thus upsets the natural balance, as, for

instance, mentioned by Sophocles:

ὕβρις φυτεύει τύραννον:

ὕβρις, εἰ πολλῶν ὑπερπλησθῇ μάταν,

ἃ μὴ ‘πίκαιρα μηδὲ συμφέροντα,

ἀκρότατον εἰσαναβᾶσ᾽

αἶπος ἀπότομον ὤρουσεν εἰς ἀνάγκαν,

ἔνθ᾽ οὐ ποδὶ χρησίμῳ

χρῆται [5]

It therefore not surprising that Heraclitus considers, as

expressed in fragment 112, the best person – the person with the

most excellent character (that is, ἀρετὴ) – is the

person who, understanding and appreciating their own true nature

as a thinking being (someone who can give names to – who can

denote – beings, and express or recount that denoting to others),

also understands the balance of Being, the true nature of beings

[cf. fragment 1 - κατὰ φύσιν διαιρέων ἕκαστον], and who

thus seeks to avoid committing the error of hubris, but who can

not only also forget this understanding, and cease to remember

such reasoning:

τοῦ δὲ λόγου τοῦδ᾽ ἐόντος ἀεὶ ἀξύνετοι γίνονται ἄνθρωποι

καὶ πρόσθεν ἢ ἀκοῦσαι καὶ ἀκούσαντες τὸ πρῶτον [6]

but who can also deliberately, or otherwise, conceal what lies

behind the names (the outer appearance) we give to beings, to

'things'.

DW Myatt

2455369.713

Notes:

[1] Fragmentum B 112 - Fragmente der

Vorsokratiker, ed. H. Diels, Berlin 1903

[2] "In Priene was born someone named and recalled as most worthy

– Bias, that son of Teutamas."

[3]

We have many ways to conceal – to name – certain things

And the skill when we wish to expose their meaning

[4] Odyssey, Book 10, vv. 302-3

[5] "Insolence plants the tyrant. There is insolence if by a

great foolishness there is a useless over-filling which goes

beyond the proper limits. It is an ascending to the steepest and

utmost heights and then that hurtling toward that Destiny where

the useful foot has no use…" (Oedipus Tyrannus, vv.872ff)

[6] "Although this naming and expression, which I explain, exists

– human beings tend to ignore it, both before and after they have

become aware of it." (Fragment 1)

Φύσις κρύπτεσθαι φιλεῖ

Physis, Nature,

Concealment, and Natural Change

The phrase Φύσις κρύπτεσθαι φιλεῖ – attributed to

Heraclitus [See Note 1] – is often translated along the following

lines: Nature loves to conceal Herself (or, Nature loves to hide).

Such a translation is somewhat inaccurate, for several reasons.

First, as used here, by Heraclitus, the meaning of Φύσις

is rather different from his other usage of the term, as such

usage is known to us in other fragments of his writings. For the

sense here is of Φύσις rather than φύσις – a

subtle distinction that is often overlooked; that is, what is

implied is that which is the origin behind the other senses, or

usages, of the term φύσις.

Thus, Φύσις (Physis) is not simply what we understand

as Nature; rather, Nature is one way in which Φύσις is

manifest, presenced, to us: to we human beings who possess the

faculty of consciousness and of reflexion (Thought). That is, what

we term Nature [See Note 2] has the being, the attribute, of

Physis.

As generally used – for example, by Homer – φύσις

suggests the character, or nature, of a thing, especially a human

being; a sense well-kept in English, where Nature and nature can

mean two different things (hence one reason to capitalize Nature).

Thus, we might write that Nature has the nature of Physis.

Second, κρύπτεσθαι does not suggest a simple

concealment, some intent to conceal – as if Nature was some

conscious (or anthropomorphic) thing with the ability to conceal

Herself. Instead, κρύπτεσθαι implies a natural tendency

to, the innate quality of, being – and of becoming – concealed or

un-revealed.

Thus – and in reference to fragments 1 and 112 – we can

understand that κρύπτεσθαι suggests that φύσις

has a natural tendency (the nature, the character) of being and of

becoming un-revealed to us, even when it has already been

revealed, or dis-covered.

How is or can Φύσις (Physis) be uncovered? Through λόγος

(cf. fragments 1, and 112).

Here, however, logos is more than some idealized (or moralistic)

truth [ ἀληθέα ] and more than is implied by

our term word. Rather, logos is the activity, the

seeking, of the essence – the nature, the character – of things [

ἀληθέα akin to Heidegger's revealing] which essence also

has a tendency to become covered by words, and an abstract (false)

truth [ an abstraction; εἶδος and ἰδέα ] which

is projected by us onto things, onto beings and Being.

Thus, and importantly, λόγος – understood and applied

correctly – can uncover (reveal) Φύσις and yet

also – misunderstood and used incorrectly – serve to, or be

the genesis of the, concealment of Φύσις. The correct

logos – or a correct logos – is the ontology of Being,

and the λόγος that is logical reasoning is an essential

part of, a necessary foundation of, this ontology of Being, this

seeking by φίλος, a friend, of σοφόν. Hence,

and correctly, a philosopher is a friend of σοφόν who

seeks, through λόγος, to uncover – to

understand – Being and beings, and who thus suggests or proposes

an ontology of Being.

Essentially, the nature of Physis is to be concealed, or hidden

(something of a mystery) even though Physis becomes revealed, or

can become revealed, by means such as λόγος. There is,

thus, a natural change, a natural unfolding – of which Nature is

one manifestation – so that one might suggest that Physis itself

is this process [ the type of being] of a natural unfolding which

can be revealed and which can also be, or sometimes remain,

concealed.

Third, φιλεῖ [ φίλος ] here does

not suggest “loves” – nor even a desire to – but rather

suggests friend, companion, as in Homeric

usage.

In conclusion, therefore, it is possible to suggest more accurate

translations of the phrase Φύσις κρύπτεσθαι φιλεῖ. All

of which correctly leave Φύσις untranslated (as Physis

with a capital P), since Φύσις is the source of certain

beings [or, to be precise, Physis is the source of, the being

behind, our apprehension of certain beings] of which being Nature

is one, and of which our own, individual, character, as a

particular human being, is another.

One translation is: Concealment accompanies Physis. Or:

Concealment remains with Physis, like a friend. Another is: The

natural companion of Physis is concealment.

Or, more poetically perhaps, but much less literally, one might

suggest: Physis naturally seeks to remain something of a

mystery.

DW Myatt

2010

Notes:

[1] Fragmentum B 123 – Fragmente der

Vorsokratiker ed. H. Diels, Berlin 1903. If the first

letter of φύσις is not capitalized, then the phrase is

φύσις κρύπτεσθαι φιλεῖ

Heraclitus flourished c. 545 – 475 BCE.

[2] Nature can be said to be both a type of being, and that

innate, creative, force (that is, ψυχή) which animates

physical matter and makes it living.

Heraclitus

- Notes on

Fragment 53

Πόλεμος πάντων μὲν πατήρ ἐστι, πάντων δὲ βασιλεύς, καὶ τοὺς

μὲν θεοὺς ἔδειξε τοὺς δὲ ἀνθρώπους, τοὺς μὲν δούλους ἐποίησε

τοὺς δὲ ἐλευθέρους. Heraclitus, Fragmentum

53.

Polemos our genesis, governing us all to bring forth some gods,

some mortal beings with some unfettered yet others kept bound.

As for Πόλεμος - while Heidegger suggested a similarity

with λόγος, Πόλεμος is in my view what the

λόγος that is both causal and acausal knowing can uncover,

rather than λόγος itself. That is, the ἀρχὴ of,

the changing, the presencing and re-presencing of Being which is ψυχή

through Αἰὼν. Hence Πόλεμος is the

whole, the complete, the natural, the cosmological, process which

includes ἀρχὴ, ψυχή, Αἰὼν,

and Φύσις, and our revealing or coming-to-know these

through λόγος. That is, through that thoughtful reasoning

[σωφρονεῖν], that balance (ἁρμονίη) of both a

causal knowing and an acausal knowing. In other words, by means of

both empathy, and also by philosophy and experimental science. In

effect, Πόλεμος is an expresion of the acausality beyond

our causal ideation, the acausal nature of which both ψυχή and

Αἰὼν manifest [1].

It should be stressed that, correctly understand, Πόλεμος

is, in my opinion, neither the struggle (Kampf) of Heidegger nor the

common translation of war. Rather it suggests - as above - the

fundamental acausality beyond Phainómenon: the presencing of

Being as Change, and thus as beings, that has been interpreted,

incorrectly because via causal ideation only, as a dialectic and

thus as a conflict, or as conflict as idea. Neither is Πόλεμος

the practical combat as in the Iliad (XVIII, 106) -

contrasted with ἔρις in the next

verse [2], as it is so contrasted in Fragment 80, attributed to

Heraclitus.

As such acausality, made manifest via ψυχή, Πόλεμος

may be said to be the origin of Δίκα [3] in a similar way

to Aeschylus attributing the numinous authority of πάθει μάθος

to Zeus [4].

Thus, our own nature as mortals is that we are part of this acausal

change - we have our genesis (both our life, and our type of living)

in this change, in and through and because of Πόλεμος.

David Myatt

2011 CE

[1] See, for example, my essays, On The Nature of Abstraction,

and Empathy and the Immoral Abstraction of Race.

[2] οῖος ἐὼν

οἷος οὔ τις Ἀχαιῶν χαλκοχιτώνων

ἐν πολέμῳ: ἀγορῇ δέ τ᾽ ἀμείνονές εἰσι καὶ ἄλλοι.

ὡς ἔρις ἔκ τε θεῶν ἔκ τ᾽ ἀνθρώπων ἀπόλοιτο

καὶ χόλος

[3] For a brief overview of Δίκα, see my essay, On The

Nature of Abstraction.

[4] Refer, for example, to my From Aeschylus To The Numinous Way.

The Abstraction of Change as Opposites and Dialectic

I - Opposites and Dialectic as Abstractions

II - The Error of Polemos as Kampf

III - Being and Empathy

I - Opposites and Dialectic as Abstractions

For well over a hundred years there has been a belief that some kind

of process, or dialectic, between or involving certain, particular,

opposites might lead us to answer questions such as Quid est

Veritas?, could lead to a certain understanding of ourselves,

and may well express something of the true nature of reality, of

Being itself. In varying degrees this belief is evident, for

instance, in Hegel, Nietzsche (with his Wille zur macht),

Marx, and those espousing the doctrine that has been termed Social

Darwinism.

In addition, and for a much greater span of causal Time, this belief

has been an essential part of certain religions where the process is

often expressed eschatologically and in a conjectured conflict

between the abstract opposites of 'good' and 'evil', God and Devil,

and such things as demons and angels.

This notion of opposites, of two distinct, separate, things is much

in evidence in Plato, and indeed, philosophically, the separation of

beings from Being by the process of ideation and opposites may be

said to have begun with Plato. For instance, he contrasts πόλεμος

with στάσις (Conflict/strife contrasted with

stasis/stability) thus:

ἐπὶ μὲν οὖν τῇ τοῦ οἰκείου ἔχθρᾳ στάσις κέκληται, ἐπὶ

δὲ τῇ τοῦ ἀλλοτρίου πόλεμος.

Rep. V 470b

In respect of these two forms, Plato tries to explain that while

there are two terms, two distinct namings - πόλεμος and στάσις

- what are so denoted are not just two different names but express

what he regards as the reality - the being, οὐσία - of two differing contrasted beings;

that is, he posits what we would call two different ideations, or

abstractions, creating an abstract (idealized) form for one and an

abstract (idealized) form for the other.

Some centuries later, Diogenes Laërtius - apparently

paraphrasing Heraclitus - wrote in his Lives

of Eminent Philosophers:

πάντα δὲ

γίνεσθαι καθ᾽

εἱμαρμένην καὶ

διὰ τῆς ἐναντιοδρομίας ἡρμόσθαι

τὰ ὄντα

(ix. 9)

All by genesis is appropriately apportioned [separated into

portions] with beings bound together again by enantiodromia [1].

Which might seem to suggest that a certain mis-understanding of

Heraclitus [2]. the ideation of Plato and of later philosophers and

theologians, was the genesis of abstractions and of this belief that

a so-called conflict of opposites can lead to 'truth', and explain

the nature of Being and beings.

However, this ideation, this

development of abstractions, and this process of a dialectic, led to

the philosophical error of the separation of beings from Being so

that instead of the revealing that would answer Quid

est Veritas? there is ὕβρις

with the numinous authority of an individual πάθει μάθος

replaced by adherence to some dogmatic dialectical process involving

some assumed struggle/conflict. That is, by considering ἀρχὴ

as the cause of the abstractions which are opposites and the origin

of a dialectic, and which opposites, and which dialectic

involving them, are said to manifest the nature of both our being

and of Being itself.

This is an error because Πόλεμος is neither kampf nor

conflict, but rather - as the quote from Diogenes Laërtius

suggests - what lies behind or beyond Phainómenon; that is,

non-temporal, non-causal, Being which, though we have have a natural

tendency to separate into portions (that is, to perceive beings as

only beings), beings themselves become revealed as bound together

again by us facing up to the expected contest: that is, to our human

nature and to knowing, to developing, to using, our faculty of

reasoned judgement - σωφρονεῖν - to uncover, to reveal,

via λόγος, the true nature of Δίκα and thus

restore ἁρμονίη [3].

That is, instead of this abstraction of a dialectic there is, as I

have suggested elsewhere:

A natural process of Change, of ἀρχὴ which we

apprehend as Φύσις - as Heraclitus expressed in

fragment 112:

σωφρονεῖν ἀρετὴ μεγίστη, καὶ σοφίη ἀληθέα λέγειν

καὶ ποιεῖν κατὰ φύσιν ἐπαίοντας.

This suggests that what is most excellent [ ἀρετὴ ]

is thoughtful reasoning [σωφρονεῖν] – and that such

thoughtful reasoning is a process which not only expresses and

uncovers meaning, but which is also in accord with, in harmony

or in sympathy with, φύσις – that is, with our own

nature as mortals and with the nature of Being itself. [4]

II - The Error of Polemos as Kampf

In a fragment attributed to Heraclitus [5] Πόλεμος is

generally regarded as a synonym for either kampf, or more generally,

for war; with the fragment then considered to mean something such

as: strife (or war) is the father of every-thing. This

interpretation is said to compliment another fragment attributed to

Heraclitus:

εἰδέναι δὲ χρὴ τὸν πόλεμον ἐόντα ξυνόν, καὶ δίκην

ἔριν, καὶ γινόμενα πάντα κατ΄ ἔριν καὶ χρεώμενα [χρεών].

Fragmentum 80.

This is generally considered to mean something abstract such as: war

is everywhere and strife is justice and all that is arises and

passes away because of strife.

However, I contend that this older understanding of - the accepted

rendition of - Πόλεμος is a misinterpretation of Πόλεμος

[6], and that rather than kampf (struggle), or a general type

of strife, or what we now associate with the term war, Πόλεμος

implies the acausality (a simultaneity) beyond our causal ideation,

and which ideation has separated object from subject, and often

abstracted them into seemingly conflicting opposites. Hence my

interpretation of Fragmentum 53:

Πόλεμος πάντων μὲν πατήρ ἐστι, πάντων δὲ βασιλεύς, καὶ τοὺς

μὲν θεοὺς ἔδειξε τοὺς δὲ ἀνθρώπους, τοὺς μὲν δούλους ἐποίησε

τοὺς δὲ ἐλευθέρους.

Polemos our genesis, governing us all to bring forth some gods,

some mortal beings with some unfettered yet others kept bound.

Hence also my interpretation of εἰδέναι δὲ χρὴ τὸν πόλεμον ἐόντα

ξυνόν, καὶ δίκην ἔριν, καὶ γινόμενα πάντα κατ΄ ἔριν καὶ χρεώμενα

[χρεών] as:

One should be aware that Polemos pervades, with discord

δίκη, and that beings are naturally born by discord. [7]

Thus the

suggestion is that Πόλεμος is not some abstract 'war' or

strife or kampf, but not only that which is or becomes the genesis

of beings from Being, but also that which manifests as δίκη

and accompanies ἔρις because

it

is

the

nature

of

Πόλεμος that beings, born because of and by ἔρις, can be returned to Being (become bound

together - be whole - again).

For it is perhaps interesting that in the recounted tales of Greek

mythology attributed to Aesop, and in circulation at the time of

Heraclitus, a personified πόλεμος (as the δαίμων

of kindred strife) married a personified ὕβρις (as the δαίμων

of arrogant pride) [8] and that it was a common folk belief that πόλεμος

accompanied ὕβρις - that is, that Polemos followed Hubris

around rather than vice versa, causing or bringing ἔρις.

As a result of ἔρις, there often arises πάθει μάθος

- that practical and personal knowing, that reasoned understanding

which, according to Aeschylus [9] is the new law, the new

understanding, given by Zeus to replace the older more religious and

dogmatic way of fear and dread, often viewed as Μοῖραι

τρίμορφοι μνήμονές τ᾽ Ἐρινύες [10]. A new understanding which

Aeschylus saught to explain in the Oresteia.

III - Being and Empathy

This new understanding is basically the culture of ἀρετή:

This culture of ἀρετή is a particular balance -

born from πάθει μάθος (from the personal knowing of the

error, the unbalance, that is ὕβρις) and from using

reasoned judgement (σωφρονεῖν), and both of which make us

aware of the true nature of our φύσις and of Φύσις

itself. [11]

In addition, by cultivating and by using our natural faculty of

empathy, which is part of λόγος [12], we can understand

both φύσις and Πόλεμος, and thus

apprehend Being as Being, and the nature of beings - and in

particular the nature of our being, as mortals. For empathy reveals

to us the acausality of Being [13] and thus how the process of

abstraction, involving as it does an imposition of causality and

separation upon beings (and the ideation implicit on opposites and

dialectic), is a covering-up of Being and of Πόλεμος and

thus involves a mis-understanding of both Δίκα and of φύσις.

In place of the numinosity of ψυχή - of Life qua being -

there is, for the apprehension that is a dialectic of opposites, the

hubris of abstractions, and thus a loss of our natural

balance, a loss of ἁρμονίη [14] and συμπάθεια.

David Myatt

April 2011 CE

Notes

[1] I have used a transliteration of the compound Greek word - ἐναντιοδρομίας - rather than given a

particular translation, since the term enantiodromia in my view

suggests the uniqueness of expression of the original, and which

original in my view is not adequately, and most certainly not

accurately, described by a usual translation such as 'conflict of

opposites'. Rather, what is suggested is 'confrontational

contest' - that is, by facing up to the expected/planned/inevitable

contest.

Interestingly, Carl Jung - who was familiar with the sayings of

Heraclitus - used the term enantiodromia to describe the emergence

of a trait (of character) to offset another trait and so restore a

certain psychological balance within the individual.

[2] Refer to my (a) The Balance of Physis –

Notes on λόγος and ἀληθέα in Heraclitus; (b)Heraclitus - Notes

on Fragment 53; (b) Πόλεμος and Δίκη in

Heraclitus B80 (forthcoming); (c) Physis, Nature,

Concealment, and Natural Change.

[3] While Φύσις (Physis) has a natural tendency to become

covered up (Heraclitus, Fragment 123) it can be uncovered through λόγος

and πάθει μάθος.

[4] In Empathy and The Immoral Abstraction of Race

[5]

Πόλεμος πάντων μὲν πατήρ ἐστι, πάντων δὲ βασιλεύς, καὶ τοὺς μὲν

θεοὺς ἔδειξε τοὺς δὲ ἀνθρώπους, τοὺς μὲν δούλους ἐποίησε τοὺς δὲ

ἐλευθέρους. Fragmentum 53.

[6] See my Heraclitus - Notes on Fragment 53, and my Πόλεμος

and Δίκη in Heraclitus B80.

In the former article, I suggest a new interpretation of Fragmentum

53: Polemos our genesis, governing us all to bring forth some

gods, some mortal beings with some unfettered yet others kept

bound.

[7] I have deliberately transliterated (instead of translated)

polemos, and left δίκη as δίκη. In respect of δίκη,

see my essay Quid Est Veritas?

Alternative renderings of the fragment are:

One should be aware that polemos is pervasive; and discord δίκη,

and that beings [our being] quite naturally come-into-being

through discord

One should be aware that polemos pervades; with discord δίκη,

and that all beings are begotten because of discord.

[8] Correctly understood, a δαίμων is not one of the

pantheon of major Greek gods - θεοί - but rather a lesser

type of divinity who might be assigned by those gods to bring good

fortune or misfortune to human beings and/or watch over certain

human beings and especially particular numinous (sacred) places.

In addition, Polemos was originally the δαίμων of kindred

strife, whether familial, or of one's πόλις

(one's clan and their places of dwelling). Thus, to describe

Polemos, as is sometimes done, as the god of conflict (or war), is

doubly incorrect.

It is interesting to observe how the term δαίμων - with and

after Plato, and especially by its (mis) use by the early Christian

Church - came to be a moral abstraction, used in a bad sense (as

'demon'), and contrasted with another moral abstraction, that of

'angels'. Indeed, this process - this change - with this particular

term is a reasonable metaphor for what we may call the manufacture

and development of abstractions, and in which development the

ontology and theology of an organized monotheistic religion played a

not insignificant part.

[9] Agamemnon,174-183. qv. my essay, From Aeschylus To The

Numinous Way - The Numinous Authority of πάθει μάθος

[10] Aeschylus (attributed), Prometheus Bound, 515-6

[11] Myatt, David: Quid Est Veritas? (2011)

[12] As mentioned in my Pre-Socratic Philosophy, The Numinous

Way, Aesthetics, and Other Questions, λόγος is

manifest to us in both empathy and reason.

[13] qv. Some Notes Concerning Causality, Ethics, and Acausal

Knowing.

[14] "...the numinous is what predisposes us not to

commit ὕβρις – that is, what continues or maintains or

manifests ἁρμονίη and thus καλλός;

the natural balance – sans abstractions – that enables us

to know and appreciate, and which uncovers, Φύσις and λόγος,

and τὸ καλόν." Pre-Socratic

Philosophy, The Numinous Way, Aesthetics, and Other Questions

The Principle of Δίκα

Δίκα is that noble, respectful, balance

understood, for example, by Sophocles (among many others) - for

instance, Antigone respects the natural balance, the customs and

traditions of her own numinous culture, given by the gods, whereas

Creon verges towards and finally commits, like Oedipus in Oedipus

Tyrannus, the error of ὕβρις and is thus "taught a

lesson" (just like Oedipus) by the gods because, as Aeschylus wrote

[1] -

Δίκα δὲ τοῖς μὲν παθοῦσ-

ιν μαθεῖν ἐπιρρέπει

In respect of Δίκα, I write - spell - it thus in this

modern way with a capital Δ to intimate a new, a particular and

numinous, philosophical principle, and differentiate it from the

more general δίκη. As a numinous principle, or axiom, Δίκα

thus suggests what lies beyond and what was the genesis of δίκη

personified as the goddess, Judgement – the goddess of

natural balance, of the ancestral way and ancestral customs.

Thus, Δίκα implies the balance, the reasoned judgement,

the thoughtful reasoning – σωφρονεῖν – that πάθει

μάθος brings and restores, and which accumulated πάθει

μάθος of a particular folk or πόλις forms the

basis for their ancestral customs. δίκη is therefore,

as the numinous principle Δίκα, what may be said to be a

particular and a necessary balance between ἀρετή and ὕβρις

– between the ὕβρις that often results when the

personal, the natural, quest for ἀρετή becomes

unbalanced and excessive.

That is, when ἔρις (discord) is or becomes δίκη

– as suggested by Heraclitus in Fragment 80 [2]

-

εἰδέναι δὲ χρὴ τὸν πόλεμον ἐόντα ξυνόν, καὶ δίκην ἔριν, καὶ

γινόμενα πάντα κατ΄ ἔριν καὶ χρεώμενα [χρεών]

One should be aware that Polemos pervades, with discord

δίκη, and that beings are naturally born by discord.

David Myatt

2011

Notes

[1]

Δίκα δὲ τοῖς μὲν παθοῦσ-

ιν μαθεῖν ἐπιρρέπει

The goddess, Judgement, favours someone learning

from adversity.

Aeschylus: Agamemnon, 250-251

[2] Refer to my essay Some Notes on Πόλεμος and Δίκη in

Heraclitus B80.

cc David Myatt 2012

Fourth Edition

This work is covered by the Creative

Commons (Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0)

License and can be freely copied and distributed, under

the terms of that license.

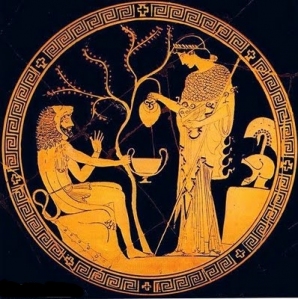

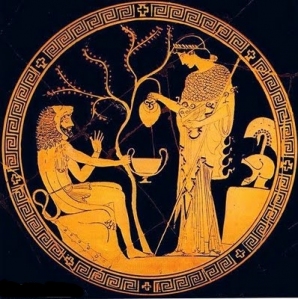

Image credit:

Attic Vase c. 480 BCE,

depicting Athena (Antikensammlungen, Munich, Germany)